Photo by Becky Duhr, courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation.

Aldo Leopold and the Land’s Original Rhythms

In 1904, after the prominent physician and Native elder Charles Eastman had visited his New Jersey boarding school, 17-year-old Aldo Leopold wrote to his parents in Iowa: “He said, after speaking of the Indian’s knowledge of nature, ‘Nature is the gate to the Great Mystery.’ The words are simple enough, but the meaning unfathomable.” Humanity has often struggled with that “unfathomable” challenge; as this passage foreshadows, few people would wrestle more eloquently with it than Aldo Leopold, who will eventually embrace Eastman’s insight. Before scholars and practitioners promoted Traditional Ecological Knowledge or Biomimicry as natural responses to environmental crises, Leopold had listened to the land’s original rhythms: “There once were men capable of inhabiting a river without disrupting the harmony of its life.”

A key figure in environmental history, Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) was a cofounder of the Wilderness Society, pioneer in game management, architect of Wilderness Areas, critic of DDT years before Rachel Carson, and an activist at grassroots and government levels. Moreover, Leopold authored many technical articles, but he is generally regarded as the voice whose 1949 book A Sand County Almanac launched the practice of environmental ethics in the 1970s, decades after his death.

Leopold was no philosopher. Educated as a forester at Yale, when Gifford Pinchot’s utilitarianism steered policy, the 22-year-old graduate stepped from the train at Holbrook, Arizona, on a summer day in 1909. He was beginning his career with the U.S. Forest Service surveying the Apache National Forest, whose boundaries had been drawn only a year before. A lover and student of the outdoors as a child in Iowa, Leopold relished his new life on horseback, surrounded by the breathtaking beauty that would be his home for the next 15 years: “I wouldn’t trade it for anything else under the sun,” he wrote upon arrival. Sadly, within a few years he’d be relegated to office work after nearly dying of kidney failure in 1913 while caught alone in flooded arroyos during a devastating hailstorm. Leopold’s journal suggests his life may have been saved by an Apache Indian, who cared for the stricken forester overnight before he could reach a doctor.

Leopold, 1909: “When I first arrived in Arizona, the White Mountain was a horseman’s world.”

Still three years from statehood when Leopold arrived in 1909, Arizona was home to about 200,000 people; its territorial neighbor, New Mexico, where Leopold lived most of his Southwest years, was only slightly larger. Connecticut, where he attended Yale, held five times as many people on five percent of Arizona’s mass. When the untried forester landed in that immense space he did not see an automobile, paved road, or substantial building, only an imposing backdrop of mountains, plateaus, and deserts, some of it Native land.

Leopold also would have seen Navajo people, who call themselves Diné, selling crafts at the railroad depot, a gateway to the new Petrified Forest National Monument. More than a few faces would have reflected their Mexican heritage. Intermarriage was common, as Leopold would attest. In 1912, he married into a Spanish land grant family that operated one of the largest sheep ranches in the country, traceable to the early 1800s. His marriage to Estella Bergere introduced Aldo not only to a new language, religion, and cuisine, but also to other ways of thinking about resources, especially water and grazing rights. Those family discussions exposed him to the land practices of other cultures.

Leopold knew he was a harbinger of change: “I am lucky to be here in advance of the big works,” he wrote home. He was living through one of the most momentous times in the history of land-management policymaking—new agencies, public lands, laws, research, disputes—and he lived where the government programs and business models were consequential. He saw the rise of tourism in the Southwest, with the hospitality entrepreneur Fred Harvey marketing exotic landscapes and peoples. It was a development not lost on Leopold, whose tourism emphasized local culture, what we’d call heritage tourism or ecotourism. Contributing to the Southwest’s touristic appeal, linguists, archaeologists, and other scientists had “discovered” Indian cultures. Alongside Edward Curtis and other photographers, scholars helped ignite an explosion of interest in Native customs and crafts, as did Mabel Dodge Luhan’s Taos artist colony, whose paintings and literature often expressed ethnic and environmental themes.

Aldo and Estella, a former teacher, lived in the middle of this, and were well-suited to the setting, joining book clubs and no doubt exploring galleries and other cultural, historic, and natural marvels. The famous Taos Pueblo was not far from the home they built as newlyweds; from their residences in Albuquerque and Santa Fe, Pueblo communities and stunning vistas were within a short ride; and the lands Leopold inspected often adjoined tribal territory, as Arizona and New Mexico contained nearly 40 reservations. In that setting where, as Eastman said, “Nature is the gate to the Great Mystery,” land and culture still intersected in revealing ways—art, architecture, food, literature. The synthesis would have a considerable effect on

Leopold’s evolution as a conservationist.

As a surveyor Leopold spent weeks riding across the Apache National Forest’s striking mountains and plateaus. Early on, he seldom passed up an opportunity to shoot a predator; after all, the Forest Service’s eradication policy ordered it, and Leopold was an experienced hunter. After one incident, however, he sensed a disconnect between his college curriculum and this hillside lesson, which likely occurred in September 1909, only months on the job.

The Black river in northeastern Arizona, where Rangers Leopold and Wheatley shot into a pack of wolves in 1909.

The Black river in northeastern Arizona, where Rangers Leopold and Wheatley shot into a pack of wolves in 1909.

The rimrocked ravine is a magnificent, grassy, tree-pocked slope to the Black River, about twenty miles southwest of Alpine, Arizona. Sitting on a boulder eating lunch while conducting a road survey, Leopold and Ranger Mike Wheatley noticed a “pile of wolves” below them at the river’s edge. Doing what they were trained and told to do—they shot at the wolves “with more excitement than accuracy,” then scampered down to the dying female, the only fatality. Leopold did not write about that experience until 35 years later in the essay, “Thinking Like a Mountain” (1944):

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain.

The mountain thinks, the wolf thinks. There is “something known” between them. Where are humans in this dialog? asks Leopold in “Thinking Like a Mountain,” a landmark in nature writing that was later collected in A Sand County Almanac.

The ebbing “green fire” in the dying wolf’s eyes had planted a thought Leopold didn’t fully grasp: that nature’s logic, what he’d call “mountain thinking,” already regulated the hillside: “there lies a deeper meaning, known only to the mountain itself.” In that moment Leopold sensed some of the “unfathomable” meaning and eventually became a voice for honoring all of nature’s “cogs and wheels,” an understanding crystalized in “The Land Ethic,” his book’s capstone essay: “In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it.”

During his nearly 40-year intellectual journey toward this statement, Leopold parted with what earlier philosophers believed about the human-nature relation, what Manifest Destiny decreed, what utilitarianism endorsed, or what many felt the Bible sanctioned. But the core of his ethic was not new, and his underlying humanistic and reciprocal tone would have been familiar to earlier cultures. In effect, Leopold crafted an ethic that is a 20th-century interpretation of the Indigenous “sacred hoop,” where all citizens of the land—humans, animals, plants—are revered. When we consider the factors that prodded Leopold toward that understanding, the cultural heritage he absorbed in the Southwest cannot be overlooked.

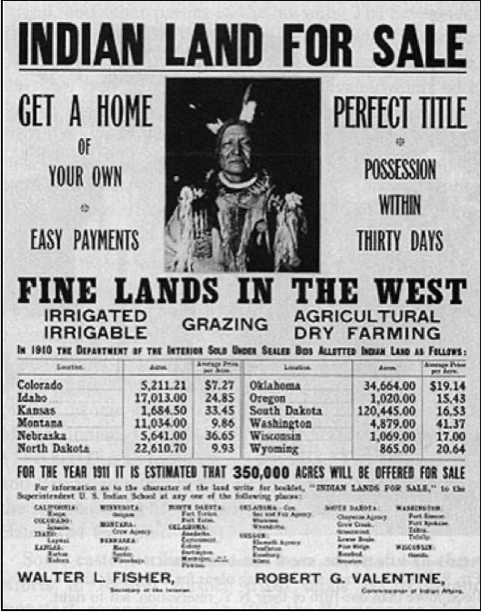

The majesty of the region extended beyond natural landscapes to cultural vistas, and when Leopold arrived, Indian nations were experiencing tremendous assaults to both their land and culture. Much of what he saw was devastating, given the inequities in education, employment, and healthcare on the reservations, often becoming worse as assimilation and termination policies swung in and out of favor. To be sure, early 20th-century reservations were desperate places, fixed in neglect and voicelessness. Upon arriving in 1909, Leopold would have learned that Arizona’s first inhabitants were not even considered U.S. citizens, a designation they didn’t receive until 1924, the year he left the Southwest. The original Americans would not be granted the right to vote in Arizona and New Mexico until 1948, the year Leopold died.

During his 15 years in the Southwest, Leopold witnessed the unrelenting theft of Indian lands.

He was among the sympathetic voices who wondered if Indigenous cultures would survive. By 1900, at least 65% of Native peoples had been wiped out since contact, with some studies claiming 90% or more. The loss of life from war and disease slowed as the 20th century began, but other losses continued. Considering that two-thirds of Indian land in 1887 was in the hands of non-Natives by 1934, Leopold obviously witnessed the unrelenting theft of Indian soil, which was not just stealing property but identity, an insight central to Leopold’s development. That is, the battles over tribal territory he witnessed were as much cultural as geographical—about the land’s sacred and familial purposes, not its economic potential. Leopold acknowledges he trained in “the age of engineers”—a world of grids, a linear universe answerable to cause and effect, managed by overconfident experts. Indigenous worldviews, he learns, are oral, obscure to outsiders, humble in nature’s shadow, holistic rather than causal. The shifting moral tone of Leopold’s essays in the 1920s suggests he not only understands but appreciates that the resilience Indian people demonstrated in the face of crises was grounded in a personal, not economic, relationship to the land. That personal connection wasn’t part of Yale’s curriculum, but Leopold would feel it and embrace it.

As head of public relations Leopold operated at the center of political, environmental, and cultural conflicts over land. He could not have failed to recognize the clash of values embedded in the battles, such as the establishment of Grand Canyon, which required the relocation of Havasupai Indians; the 1922 Colorado River Compact in Santa Fe, which ignored Indian rights; or amendments to the Dawes Act, which tried to turn tribes into yeoman farmers. The turmoil occurring on Indian land with new laws, ranching and recreation, and corporations clawing at resources, drew Leopold into the controversies, especially because the disputes, laws, treaties, and dispossessions concerned land, culture, and politics, three topics that consumed him.

Leopold’s earliest writings reflect agency practice, viewing Natives as obstacles to well-ordered landscapes, and his words are cringe-worthy. While crafting plans for the Grand Canyon in 1915, he wonders, “Quite a question about how to handle the Supai Indians,” dismissing the tribe’s historic bond to the gorge. However, always responsive to cultural stimuli, which weave through his letters and journals, Leopold’s essays begin to question federal policy in language that is more personal and philosophical. Julianne Newton observes about his final years in the Southwest that cultural expressions, the point of contention in many disputes, elbow their way into Leopold’s thinking, where answers “would involve cultural as well as ecological insights.” He’d begun to refer to “land health” in terms that stressed ecological and moral obligations. “The result,” says Curt Meine, “was a series of articles and speeches noteworthy for ecological insights decades ahead of their time.” These insights also reflect his growing appreciation of earlier cultures: “Five races—five cultures—have flourished here,” he writes in 1923. “We may truthfully say of our four predecessors that they left the earth alive, undamaged.”

It’s no exaggeration to suggest that the culmination of Leopold’s journey, his Land Ethic, had its genesis in the Southwest. Granted, when he left for Wisconsin he wasn’t close to articulating his famous statement, but he’d taken steps—questioning policies concerning fire, sustained yield, road building, predator control, and the value of wilderness. He had spent 15 years exploring, studying, writing about, and learning from a natural and cultural environment very different from Iowa. That sense of place, where Indigenous and Mexican traditions still influenced land policy, and society itself, would have a lasting effect as Leopold traveled north in 1924 to work at the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin. He quit that job in five years and became a “consulting forester” on the eve of the Depression.

•

Leopold’s Southwest education will be reinforced in Wisconsin—the result of a frustrating job, economic worries, ecological failures, looming wars, and, close to home, felled forests absent an Indigenous population. By the time of Statehood in 1848, Wisconsin had rid itself of many Indian lands and most native forests. Leopold saw more clearly the connection between nature and culture—and the disastrous consequences of a rupture.

On April 19, 1935, which would be called “Black Sunday,” Leopold gave a university talk titled “Land Pathology”: “Conservation is a protest against land’s destructive use.”

The economic and agricultural disasters of the 1930s tested the nation’s faith in the Progressives’ science. The Southwest had chipped away at Leopold’s confidence, and now, by way of extensive research across the Midwest, he saw ecological catastrophes engineered by “experts.” The Dust Bowl he chalked up to “clean farming,” performed by tools that are “better than we are.” The Hopi, he knew, grew corn on rock mesas with little water for millennia, yet modern farming had turned healthy soil to sand in a generation.

During a research trip to Germany in 1935, after securing a university position, Leopold saw artificial, “cubist” forests, the result of “a too purely economic determinism as applied to land use.” Initially he paid little attention to the political situation but soon learned of the “tragic story” behind the treatment Jewish citizens. Again he connected land and people, and upon returning Leopold wrote that the way we treat land speaks volumes about the way we treat society: “To change ideas about what land is for is to change ideas about what anything is for.” Anything. Everything. The sacred hoop. Nazi researchers valued trees as commodities and produced lifeless forests. Leopold knew Indigenous peoples lacked academic studies, but they possessed the wisdom “to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.”

When Leopold purchased 80 acres near Baraboo, Wisconsin, the only structure remaining was a chicken coup, which became “The Shack.”

When Leopold purchased 80 acres near Baraboo, Wisconsin, the only structure remaining was a chicken coup, which became “The Shack.”

Other lessons occurred on his own land. In 1935, Leopold bought 80 sickly acres 50 miles north of Madison, the site of his Shack, where he experimented with “working landscapes” until his death in 1948. The family’s weekend trips brought him into contact with other land owners, and cultivating a conservation ethic among the public became a cause: “There must be some force behind conservation—more universal than profit … I can see only one such force: … a sense of love and obligation.”

What drew Leopold to “love and obligation” as an organizing principle? Searching for answers to the human-nature riddle, he regularly channels his profession’s research, but, increasingly, he invokes cultural lenses: Eastern literature, Transcendentalism, Russian mysticism, western history, European philosophy, art and literature. In time, Leopold reaches back to the expressions of another place. Especially as he traveled widely inspecting farms and forests, Leopold reflected on and wrote about the unspoiled Southwest: “It was here that I first clearly realized that land is an organism and that all my life I had seen only sick land.” The tumultuous 1930s, when more than a few certainties toppled, provided an opening for Indigenous values to resurface. A noticeable outcome is that Leopold’s later comments about Natives honor their values. Elsewhere, his words seem tinged with regret for shutting out an entire culture: “It did not occur to us that we, too, were the captains of an invasion too sure of its righteousness.”

A humbled Leopold, his confidences tested more than once, accepts the “unfathomable” bond, aware that the hillside is ordered by “unknown controls” too complex to manage. Rather than “fix” nature, Leopold senses he can and should learn from it, as Black Elk counseled: “One should pay attention to even the smallest crawling creature for these too may have a valuable lesson to teach us.” Over time, the slow fusion within Leopold spawns an ethic that is, in part, a western interpretation of Indigenous land practices, made understandable and palatable to a dominant culture steeped in progress, boosterism, and scientific certainty. Given his era, it’s unlikely Leopold could stand before land managers and declare, “We came from the earth … our mother,” as did a Nez Perce prophet. But that is what his Land Ethic proposes—a community nurtured by original practices and framed by a new ecological understanding: “The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”

This land, advises Black Elk, can teach, can be read like a book—a story of the people who cared for it. Leopold emphasized the same lesson to his students: “The woodlot is, in fact, a historical document which faithfully records your personal philosophy.” This reciprocal nature of the Land Ethic underlies its defining feature, which is that our relationship to nature must be based on something other than profit. It is a quality that follows from Indigenous principles, where land was seldom a commodity to be surveyed, fenced, or purchased, an expression captured in Leslie Silko’s Ceremony:

The snow-covered mountain remained, without regard to titles or ownership or the white ranchers who thought they possessed it. They logged the trees, they killed the deer, bear, and mountain lions, they built their fences high; but the mountain was far greater than any or all of these things. The mountain outdistanced their destruction, just as love had outdistanced death. The mountain could not be lost to them, because it was in their bones.…

The mountain was in the peoples’ bones, regardless of the whites’ attempt to own and dominate it. Silko’s novel concludes on the mountain as Tayo rejoices in the universe’s wholeness—mountain thinking. Emerson found similar views in Eastern literature, and when Henry David Thoreau or Mary Austin, author of The Land of Little Rain, celebrate “Indian wisdom,” they also pay tribute to the sacred hoop. To that time-honored ethic, Leopold artfully adds ecology—reconfirming scientifically what earlier civilizations revered spiritually.

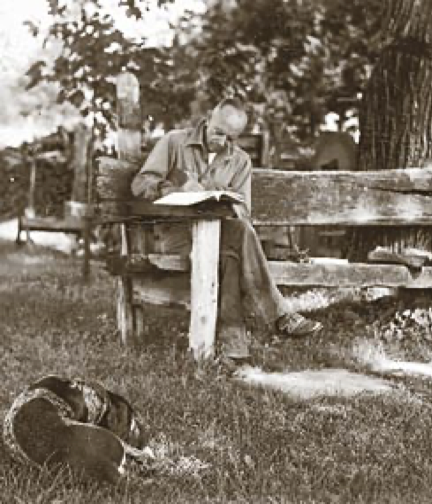

Leopold writing at The Shack, likely working on the manuscript for A Sand County Almanac, which he never saw in print.

Leopold writing at The Shack, likely working on the manuscript for A Sand County Almanac, which he never saw in print.

Like Thoreau, who died mostly unknown beyond Concord, Leopold was not well known outside forestry circles when he died in 1948, and A Sand County Almanac sold poorly when published a year later. Both men stood outside their time. Walden appeared as the Industrial Revolution was about to crown technology, and Leopold’s thoughts were stifled by a post-WWII science mania. Still, just as it took him decades to decipher his Southwest experiences, a new generation in the 1960s grasped the largely unplumbed implications of his poetry, and A Sand County Almanac emerged as one of the bibles of environmentalism, even though it eludes direct application. But the book is an inquiry, not a manual. It mirrors Robin Wall Kimmerer’s description of Indigenous instructions, which “provide an orientation but not a map.”

Leopold followed those orientations his whole life—in classrooms, publications, mountains, activism. It’s a journey he would describe but not live to read, after suffering a fatal heart attack fighting a fire near the Shack in 1948. Leopold never saw his final words in print, nor did he have any idea how A Sand County Almanac would be regarded, selling millions of copies in a dozen languages, launching university programs and conservation agencies, and encouraging countless admirers to change careers—to change themselves, because Leopold is about shaping values as much as landscapes. Conservation is a tool, a means to a greater social good.

Just as Native peoples located their identity, purpose, and future in nature, Leopold cultivates a larger moral purpose. He admonishes our hubris, suggesting most achievements are only tools that produce more tools. The depressing result is a landscape shaped by means not ends, by tools not wisdom. To prevent that, Leopold counsels, we should listen to the mountain and its partners in the soil. Importantly, we have mentors here who can teach us. If we train our ecological ear, the land may whisper and we may hear the “unfathomable”:

Then you may hear it—a vast pulsing harmony—its score inscribed on a thousand hills, its notes the lives and deaths of plants and animals, its rhythms spanning the seconds and the centuries.

Aldo Leopold heard that harmony camping along the Rio Gavilan in Mexico—land that had escaped the surveyor’s supervision and remained a “picture of pure ecological health.” The mountain knows.

For twenty years, Dan Shilling served as executive director of the Arizona Humanities Council. He went on to teach nature writing at Arizona State University and co-edit Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Stability, published by Cambridge University Press in 2018.